On the old road that connects Santa Cruz to Cochabamba, in the tropics and valleys of Bolivia, lies a small region known as the “dry inter-Andean valleys.” Towering rock formations, as imposing as they are inaccessible, stand tall. At their base, rivers and springs flow, shrubs dot the landscape, and vast expanses of fertile land offer favorable conditions for agriculture.

Back in the 60s and 70s, many parts of this area remained untouched by human hands, and large-scale commercial farming had not yet taken hold. Trees like the “chañarillo,” with its fleshy and starchy fruits, and the “cupesí” tree, provided natural sustenance for a species that thrived in the area and nested on the cliffs: the red-fronted macaw (Ara rubrogenys).

Filemón Soto, a lean and elderly man with a prominent stature and a cheerful smile, recalls flocks of parrots, as these Macaws are usually called, landing by the riverside like a green swarm that would settle momentarily before taking off again.

Over the years, the landscape of brown and reddish hills started to change. The clusters of shrubs gradually faded from memory, replaced by expanding agricultural fields. As the population grew, the availability of wild fruits diminished, leading the Red-fronted Macaws to increasingly rely on cornfields and peanut plantations for sustenance. That marked the beginning of their decline.

The struggle for survival

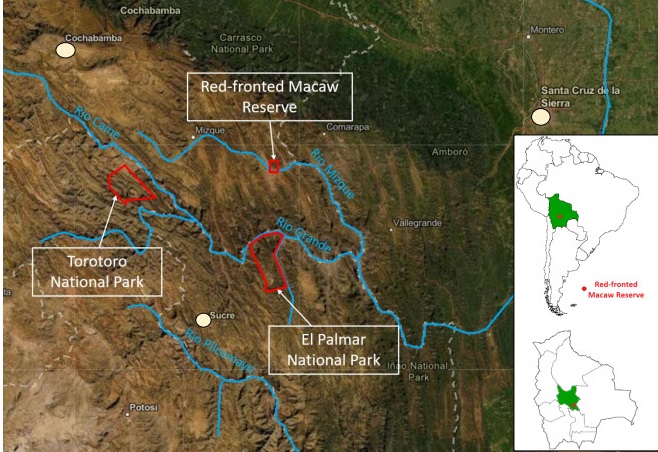

The dry inter-Andean valleys encompass four departments in Bolivia: Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, Chuquisaca, and Potosí. The Red-fronted Macaw, slightly over half a meter tall, with a green body, blue wings, and a red forehead, is endemic to this region. Its only nesting site of significant importance lies within a community of no more than 40 families called San Carlos. Located five hours from Cochabamba, this village is adjacent to Perereta and Amaya, two other Quechua communities. Together, these three communities form the Perereta Peasant Subcentral, which falls under the jurisdiction of the municipality of Omereque (Cochabamba).

Currently, almost all of the native vegetation in the valleys has been replaced by agricultural fields. The “Red-fronted Macaw Action Plan 2022-2032” states that by 2008, perhaps only the municipalities of Pasorapa and Aiquile (Cochabamba) still contained the last relatively intact dry forests in central Bolivia.

As a consequence, the populations of Red-fronted Macaws began to decline, eventually reaching a critical point where they are now considered “critically endangered” both in Bolivia and by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). This degradation of their habitat also led to other direct threats.

Between 2004 and 2007, a total of 27,535 individuals from 36 species of macaws and parrots were put up for sale in the Los Pozos market in Santa Cruz de la Sierra. This information comes from the study “Conservation Status of Birds in Bolivia,” conducted by the Civil Asociación Armonía, an organization dedicated to the conservation of these vertebrates. According to the report, the methods of capture, as well as the poor transportation and storage conditions, result in the deaths of 50% of individuals before they reach the points of sale. Of the survivors, 90% perish before reaching their final destination. This demand drives traffickers to capture large numbers of these birds.

In this context, the exotic pet markets were the main threat to the Red-fronted Macaw and two other Bolivian macaw species—Blue-throated Macaw (Ara glaucogularis) and Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus)—during the 20th and early 21st centuries. Although the international agreement on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) was signed in 1979, there was little border control until the early 21st century.

“We used to see the macaws, about 25 to 30 years ago, mainly by the river. They looked for a spot to settle and drink water. About 50 to 80 of them would come down. Outsiders would come, spy on them, lay out a net like the color of the stones, and catch them. They were taken away in boxes. They say they were sold for up to a hundred dollars, 300 (around 45 dollars), or 500 bolivianos (72 dollars),” recalls Vicente Vela Rocha, a resident of Amaya, describing the capture process. The method of capturing them was just one part of the trafficking chain. How they reached countries in Europe and the United States was another story—chicks piled into plastic tubes, traveling by plane for up to 12 hours.

This illegal market, combined with farmers’ frustration over macaws eating their crops, played a significant role in the decline of macaw populations. Often, instead of killing them, locals would capture the birds to sell them to traffickers.

For farmers like Vicente or Filemón, losing a harvest was not just an economic setback. Balancing working under scorching sun and freezing early mornings, tending to plants and watering them, all while managing household chores, took (and still takes) a toll on their physical well-being.

“We used to see them as birds ruining our crops. They would take the entire corn and not just a little bit, they would gulp it down. So, we thought how can we eliminate this animal? We never imagined it could generate income for us,” says Marlene Rivas, a resident of San Carlos.

A gradual process

That’s why, back in the 2000s, when a team from Asociación Armonía approached the farmers of San Carlos, Perereta, and Amaya to discuss conservation alternatives for the red-fronted macaw, their initial response was a resounding “no.”

“I remember that Bennett Hennessey, the organization’s Development Director, insisted that this could be seen as a site for tourism. At that time, birdwatching tourism wasn’t even a term used in Bolivia,” recalls Guido Saldaña, the current coordinator of Armonia´s Red-fronted Macaw Conservation Program.

At that time, Saldaña was a young volunteer and biology student. Coming from a farming background, he was familiar with the area. Under the guidance of biologist Abraham Rojas and with the advice of important ornithologists like Bennett Hennessey and Sebastian K. Herzog, they embarked on the journey that would lead to the creation of what is now the Red-fronted Macaw Natural Reserve. This fenced area spans 50 hectares and is not only home to the Red-fronted Macaw but also hosts 134 other bird species.

After several years of workshops, training sessions, talks, donations, meetings, and the community’s decision to participate in the construction of an ecotourism lodge, the Reserve began its operations in 2006. However, it wasn’t until 2011 that the first signs of success began to appear.

“We didn’t know it was an important bird for Bolivia; we used to kill them, or there were people who would come and catch the parrots with traps. In 2003, a small project arrived, they built that lodge, and here we are,” says Filemón Soto, now the representative of Perereta on the Reserve’s Administrative Committee.

The fruits of the Macaw

There are two types of birdwatchers, known as “birders”: those who seek to photograph specific species and the hardcore birders, whose goal is to expand their personal list of species observed throughout their lives. In both cases, while it’s becoming more common to see young enthusiasts, the majority are people over 50 with the financial means to travel to different countries and pay up to 200 dollars (or more) for a night’s lodging.

Álex Jiménez López (32), a tourism expert and Armonia’s Tourism Responsible, explains that these visitors come primarily from the United States (the largest market), Europe, and Asia. Slowly but surely, there is also a growing number of visitors from Latin America. These visitors have clear objectives and often arrive with the necessary information, their own guide, and their own transportation.

In countries like Peru and Colombia, where avitourism is well-established, these ventures are often privately run. In Bolivia, it is a community effort and has gained ground over the past ten years. This is due to the fact that the residents of these three communities share in the profits while also taking care of the macaw, respecting its habitat, and working together to improve the lodge’s infrastructure and surroundings.

According to their bylaws, the funds acquired should be allocated towards education, health, and sports. However, the final decision on how to use the funds lies with the communities themselves.

“In our case, we allocate 10% to the little school for school supplies. Another 10% is for sports tournaments, as stated in our regulations. With the rest, we improve our water supply. With the funds we received in 2022, we helped finish constructing these social housing units,” explains Cresencio Guzmán, the representative of San Carlos on the administrative committee.

In Perereta, funds from various endeavors were used to build a space at the community’s only primary school. Although it now appears deteriorated due to a lack of maintenance, it still houses children who receive their school breakfast there. Additionally, a sound system was purchased, funds were invested in public lighting, and sports clothing was bought.

As for Amaya, they received 21,000 Bolivianos (around $3,000) in 2022, “thanks to the people who come to see the red-fronted macaw,” says Vicente Vela Rocha, their representative. “With the funds that have been allocated to us, we distributed 200 bolivianos to each person (just under $300), and the rest is in the bank—nearly 45,000 bolivianos or more. We’re keeping it there to use when necessary,” he explains.

A flight of hope

The Red-fronted Macaw Community Reserve is the most important breeding site for the species, with at least 20 breeding pairs each year, according to Armonia’s “Red-fronted Macaw Program: 2022 Annual Report.” Last year, the General Directorate of Biodiversity and Protected Areas also presented the Red-fronted Macaw Conservation Action Plan 2022-2032, a document outlining conservation measures to prevent extinction.

In fact, the latest census conducted in 2021 showed that the population had increased, but the critical risk persists. One of the main causes is the loss of habitat due to intensive agriculture in the species’ distribution zone. At that time, the population was counted at 1,160 individuals, 353 more than in 2012. The hope lies in the inaccessible nesting sites, in this case, the community reserve.

The actions taken with the support of the communities have yielded results. Residents of San Carlos, Perereta, and Amaya now speak of the Red-fronted Macaw as a bird to be cared for, even though they admit to having harmed it in the past. The risks from poachers lurking near the cliffs and rivers to snatch chicks persist. As a result, the local community helped protect the reserve by installing wire mesh, for instance.

Reproductive activity of the Red-fronted Macaw

Monitoring nests in the Red-fronted Macaw Reserve in Cochabamba

Inside the reserve, efforts to cultivate peanuts and reforest with chañarillo trees, one of the macaw’s preferred foods, have begun. Last June, during an assessment meeting for the lodge’s results and situation, representatives from the three communities decided—for the first time—to go out and purchase the necessary supplies for renovations and improvements. While this activity may seem minor, it is a significant step toward allowing them to eventually manage the reserve autonomously.

After multiple visits and tours of the communities and the residents’ farmland, the question remains whether they will take on this challenge on their own one day.

“We still don’t have the capacity to maintain the reserve, but we’re learning. Years before, we didn’t even know where to begin; they (the Armonía team) helped us, brought us what we needed. On July 5th, we went to Cochabamba for the first time to do some shopping. Now we know prices, where we’re going to buy from. We have someone from the community in the kitchen and another in cleaning. We said that when more tourists come, other people from the community can learn; hopefully, the young ones will do it,” says Cresencio.

● This report was produced as part of the Journalism Solutions Fund, organized by the Foundation for Journalism, with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

This post is also available in:  Español

Español